LLMs

An overview of large language models (LLMs), covering LLM prompting, LLM fine-tuning, and LLM application development.

Large language models (LLMs) are AI models that are intended to comprehend and generate human language, code, and much more. They are typically derived from the Transformer architecture. This architecture was introduced by a team at Google Brain in 2017. Attention, transfer learning, and scaling up neural networks are the main principles that lay the groundwork for Transformers to flourish.

Pretrained LLMs: Efficiency

Pretrained LLMs, such as OpenAI's GPT-4 and GPT-3, Meta's LLaMA, Google's PaLM, Flacon, etc., are models with sizes of billions of parameters, and for some, the size exceeds 50 billion or even 100 billion parameters. This means we need a large memory capacity to train such models : tens of thousands of gigabytes. This is quite expensive and requires access to hundreds of GPUs (+ high carbon footprint).

Recent research studies have looked at the relationship between model size (number of parameters), the dataset size used to train the LLM model, and its performance. Is it true that the performance will be enhanced by increasing model parameters? How big is the dataset, exactly? What happens if the dataset size used to train the LLM is increased? What is the ideal ratio between these two key elements?

A team of academics from DeepMind conducted in-depth research on the performance of large language models with various model sizes (number of parameters) and training dataset sizes. The results were published in the paper "Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models" in 2022 . The ideal model produced by the author's work is called "Chinchilla".

The most important key lesson from the Chinchilla research is that the best size of the training dataset for a given LLM model is about 20 times larger than the model's parameters number. The ideal training dataset (for the best compute optimal model Chinchilla) has 1.4 trillion tokens for 70 billion parameters, as depicted in Table-2, above.

Important finding: Just one year after the publication of the Chinchilla Paper, Meta AI makes available its state-of-the-art large language model, LLaMA-65B. This model was trained using a dataset that was roughly 1.4 trillion tokens in size, which is similar to Chinchilla's suggested number.

Prompt Engineering

Sometimes using these state-of-the-art pretrained LLMs for inference leads to undesirable results right away. To get the model to behave in the desired manner, we might need to make multiple revisions to the language or format of our prompt. The process of creating and enhancing the prompt is referred to as prompt engineering.

Basic Methods: Zero-shot, one-shot & few-shot prompting

Zero-shot prompting:

Zero-shot prompting refers to giving the model a prompt (task) that isn't part of the training data but can nonetheless lead to the desired output. For example, in the case of sentiment analysis, we are aware that the ideal method for classifying reviews is to train a machine learning model on labeled data in order to obtain the appropriate result for an as-yet-unseen review in inference. However, LLMs are not trained in this way or to perform this task, but if we ask them to perform classification tasks, they can still deliver the desired results. Here's an example of Zero-shot prompting:

Classify this review: I love red apples Sentiment:

One-shot prompting & few-shot prompting

Performance can be enhanced by one-shot prompting, where we can guide the LLM with an example of the desired behavior within the prompt.

Classify this review: I love red apples Sentiment: positive

Classify this review I adore vegetables Sentiment :

Sometimes providing one example is not enough. For the example of sentiment analysis, we can provide a prompt with two examples (or more): one positive and the other negative. This is few-shot prompting.

Important finding According to a study that was released in 2020, "Language Models are Few-Shot Learners", most large language models are quite good at inference with few-shot prompting. This paper examines the potential of few-shot prompting in LLMs.

Chain of Thought (CoT)

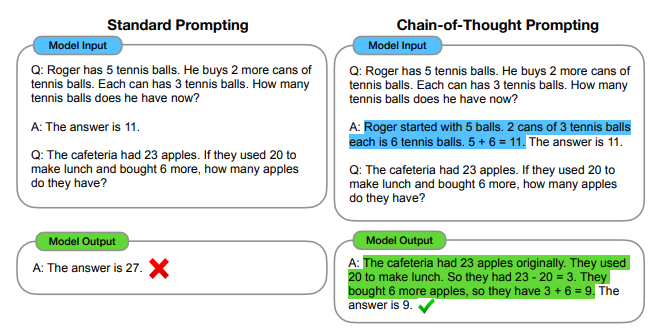

A prompting method used to assist LLMs in reasoning is Chain of Thought. Making the model think more like a human by breaking the task down into steps is one tactic that has shown some promise. When you use examples for one-shot or few-shot inference, it works by incorporating a number of intermediate reasoning steps.

The example below, which is derived from the paper "Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models,2023", published by researchers at Google, demonstrates how the LLM's behavior was completely changed when a standard one-shot prompt (simply giving the answer) was replaced with a chain of thought prompt by including the reasoning steps that solve the problem. This helped the LLM succeed by implicitly asking him to mimic human behavior.

Reasoning & Acting (ReAct)

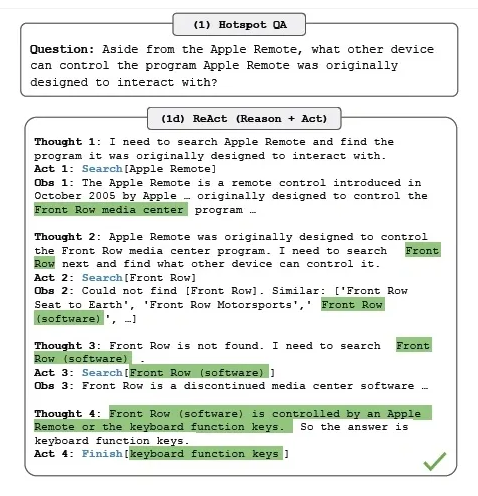

ReAct was created by researchers from Google and Princeton, in 2022. It was proposed in the paper "ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models, 2022". It is a cutting-edge prompting technique that is being used by frameworks that communicate with LLMs, such as LangChain. It is an iterative process that requires calling the LLM to get a "thought" and an "action" (trying to solve the task asked by the user). This action would be executed by accessing external sources via an implemented tool that communicates between the LLM, the user App (where you write the prompt), and the real world (external data from the web, for example, or external APIs). It's usual to refer to this intermediary tool as a technology implemented in the orchestration library. The outcome of this first action is called "observation". The ensemble of the first thought, the first action, and the first observation will construct the context for the second LLM's iteration (call). As a matter of fact, depending on this context (Thought1 + Action1 + Observation1), the LLM will generate a second thought and a second action trying to solve the task (asked by the user), then it executes this newly generated second action using the orchestration tool to collect a second observation. If the problem (task) is not resolved by this second observation, the process of coming up with thoughts and actions (and carrying them out) will go on until the problem (the task) is resolved.

As you have certainly noticed, ReAct is a technique based on the capacity of human intelligence to integrate verbal reasoning with task-oriented actions (exactly mimicking human behavior when solving a problem).

Here is an example that was taken from the original paper that introduced the ReAct paradigm, published in 2022 (mentioned above).

Fine-tuning LLMs: Low-rank Adaptation LoRA

When creating an LLM-powered app, working with pre-trained LLMs can help us save a lot of time. However, if our target area employs uncommon terminology, we might find it necessary to fine-tune LLMs based on specialized data. For instance, if we have to create a medical app powered by LLMs, typically, medical terminology uses many rare phrases to describe medical diseases and procedures that may not be regularly found in the training datasets (web scrapes and book texts) used to train LLMs. Thus, fine-tuning LLMs with specialized data will result in better models for our LLM-powered apps.

A group of methods known as parameter-efficient fine tuning trains only a limited subset of task-specific layers and parameters while maintaining most of the weights of the original LLM (or even all the original weights with LoRa). Since all or the majority of the pre-trained weights remain constant, these methods exhibit greater resistance against the well-known catastrophic forgetting phenomenon, which happens when a fully finetuned LLM loses its primary capabilities after updating its weights. There are several parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods.

How does Low-rank Adaptation (LoRA) work?

LoRa simply adds a minimal number of new parameters and fine-tunes them, leaving the existing original model weights untouched (frozen). LoRa injects two low rank decomposition matrices. These two new small matrices should be designed with dimensions such that the resulting matrix (their multiplication) has the same dimensions as the original weights matrix. Then, as previously stated, we just train these two low-rank matrices on the new data (the new task) while maintaining the original weights of the LLM frozen.

For inference, these two trained low-rank matrices are multiplied in order to produce a matrix with the same dimensions as the frozen weights. After that, we add this to the initial weights and update the model to reflect these new values (the sum of the original weights and the new trained weights). This is the LoRA-fine-tuned model that can complete our particular task. Depending on our new task and data, we can train as many LoRA matrices as we need: all we have to do is add these updated weights to the initial frozen weights each time and run the inference with the new model.

The new LoRa variant QLoRA, which is LoRa fine-tuning method but based on quantization, is introduced in the paper "QLoRA: Efficient Finetuning of Quantized LLMs", which was just released (May 2023). Quantization transforms the model's weights to a lower precision representation.

The authors named their best QLoRa fine-tuned model Guanaco. On the Vicuna benchmark, "it exceeds all prior available models, achieving 99.3% of ChatGPT's performance level with only 24 hours of fine-tuning on a single GPU." (this sentence was taken from the paper). Impressive findings. QLoRA is definitely the most effective way to fine-tune large language models on a single GPU.

Fine-tuning LLMs with Human Feedback (RLHF)

Making LLMs function in accordance with human preferences is the goal of the process known as "fine-tuning LLMs with Human Feedback". For example, we want LLMs to behave as helpful, harmless, and honest assistants. These three values harmlessness-helpfulness-honesty, are the key ones cited in most research articles when discussing fine-tuning with human feedback. As an illustration, the authors of the paper "Training a Helpful and Harmless Assistant with Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback, 2022" [10], discuss these 3 criteria and refer to them by the acronym "HHH".

Naturally, we may specify additional values that we want the LLMs to adhere to, in order to conform to human preferences (ensuring that the LLM generates completions that maximize or minimize any criteria set out by us). As an illustration, I would like the LLM to be particularly tolerant (not prejudiced or racist).

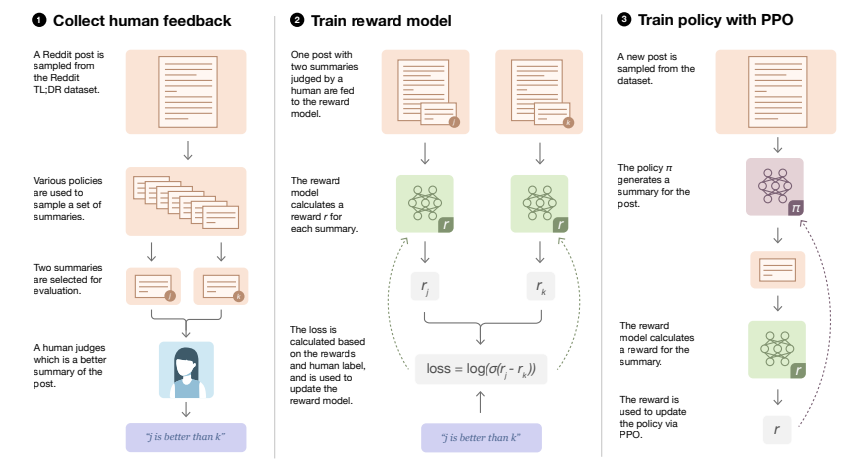

Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) is the most popular method for fine-tuning LLMs with human feedback.

RLHF is a process for fine-tuning LLMs to match human preferences. It is an iterative process (like other tuning processes). There are two central components in this process: the reward model and the reinforcement learning algorithm. The reward model outputs a reward value to the completions generated by the LLM and passes this value to the RL algorithm, which will iteratively adjust the weights of the LLM to maximize the reward obtained from human feedback, pushing the LLM to produce texts that are more aligned with the criteria we defined (for example, tolerance).

How does RLH really work?

1st step: Construct a dataset of many prompts and completions (generated by the LLM we want to fine-tune with RLHF).

2nd step: We collect feedback from humans labers that will score these completions according to the criterion we defined, let's say, tolerance, by classifying them as tolerant or non-tolerant (racist) generated texts. In fact, this step is more complicated (not straightforward, assigning many labers for each completion, etc.), and it is actually time-consuming and very expensive. At the end of this step, we get the dataset that will be used to build the reward model (one of the central components of the RLHF process), which will replace the human labers in the fine-tuning stage.

3rd step: Building the reward model (using a supervised learning model: a classifier).

4th step: The reinforcement learning finetuning process begins by passing prompts to the LLM, which generates completions. The reward model assigns a reward value to the completions (high for more tolerant text or low for less tolerant text). Then, it passes this value to the RL algorithm, which will update the weights of the LLM, pushing it to generate more aligned text with the criterion defined (tolerance in this case) to maximize the reward obtained from the reward model. This is a single iteration.

5th step : Step 4 will be repeated in an iterative manner, updating the weights of the LLM model at each iteration, until reaching a threshold already defined (for the criterion or number of iterations).

The final version of the fine-tuned LLM with Human feedback (using RL) is called human-aligned LLM: It is our ultimate goal to ensure that our LLM behaves in an aligned manner in deployment!

There are several different RL algorithms that can be used in the RLHF process. The most common one is proximal policy optimization (PPO).

Here is an illustration of the main steps of fine-tuning an LLM with human feedback using RL, derived from the paper "Learning to summarize from human feedback, 2022" [12]

Augmenting LLMs to create LLM-powered Apps : RAG

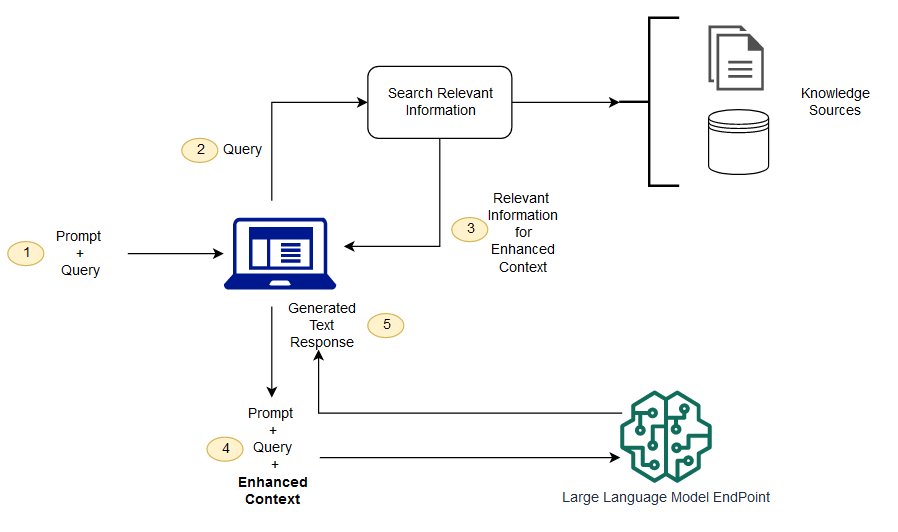

Regularly retraining LLMs with new data is ineffective as a solution. The significant carbon footprint caused by the enormous number of GPUs running continuously will make it not only incredibly expensive but also a burden for the environment and the planet. Implementing technologies that give LLMs access to external data during inference time is a more flexible and affordable technique to get around knowledge cutoffs. The best example of this, is RAG framework: Retrieval Augmented Generation.

Actually, RAG is a framework for creating LLM-powered apps that use outside data sources and get beyond the LLM's drawbacks, like information that is missing from the pre-training phase, known in some publications as the knowledge cutoff phenomenon. But not only that, RAG also gives access to external APIs and even confidential information kept in the private databases of companies and organizations (to restrict the access just to them). This is made possible through an orchestration library. This layer has the potential to enable certain potent technologies that will enhance LLM's performance. Simply said, RAG is an excellent approach to assist the LLM model in updating and broadening its view of the world !

RAG has many implementations, varying in complexity from simple to complicated. LangChain is one popular RAG implementation. The advanced prompting strategies, like ReAct, that I mentioned in paragraph-3, are effectively implemented in LangChain.

I'll be talking about the straightforward general architecture of RAG framework, that was suggested in the paper "Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks, 2021" [13], One of the earliest papers published about RAG.

The retriever is the main component of this architecture. It is a combination of a query encoder and an external data source.

How does it work ?

1st step: The encoder takes the user's prompt and converts it into a format that the external data source (which could be a database, for example) can use. In the paper, it is a vector store (vector stores allow for a quick and effective similarity-based search and are also a good data format for the LLMs because they use the same format to generate text).

2nd step: Then, it searches for relevant information, in the external sources, that matches the query (the encoded user's prompt).

3rd step: When appropriate information is discovered in the external sources, the retriever adds the new data to the initial prompt.

4th: The new enhanced prompt (the original prompt + new extracted information) is passed to the LLM, which generates the final output (completion) for the user.

This general diagram (Figure-4, below) is an illustration of the straightforward architecture of the Retrieval Augmented Generation framework (RAG).

Caching: To reduce latency and cost

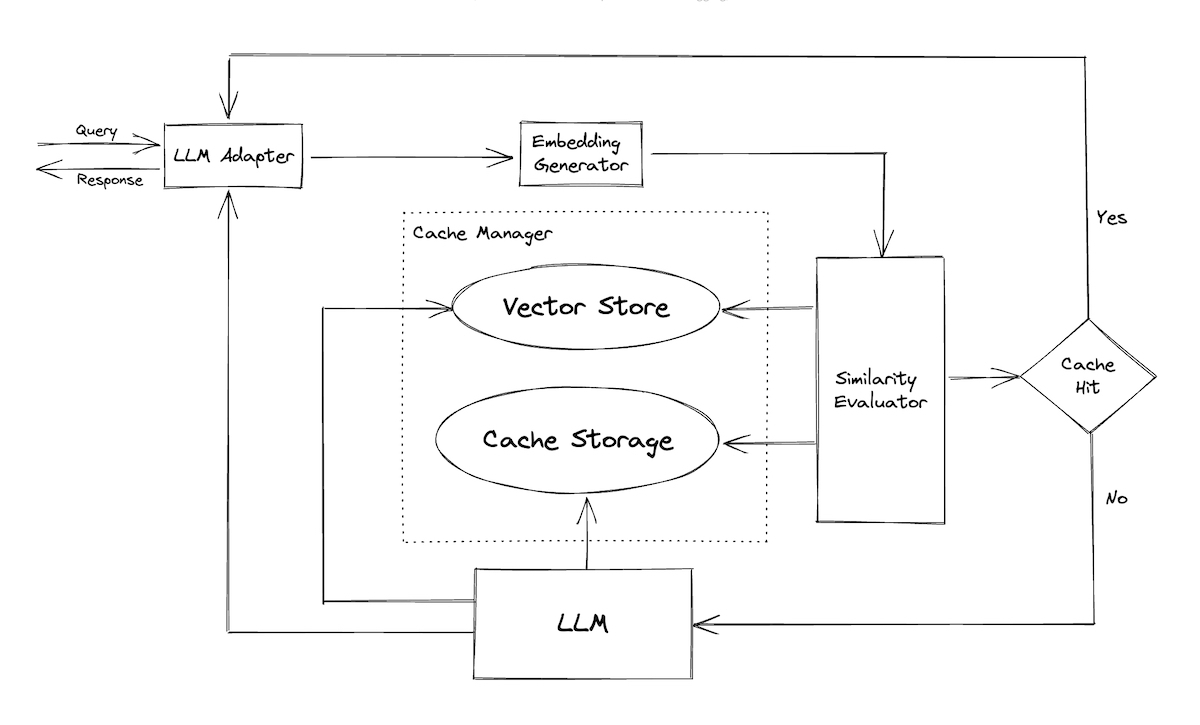

Caching is a technique to store data that has been previously retrieved or computed. This way, future requests for the same data can be served faster. In the space of serving LLM generations, the popularized approach is to cache the LLM response keyed on the embedding of the input request. Then, for each new request, if a semantically similar request is received, we can serve the cached response.

For some practitioners, this sounds like “a disaster waiting to happen.”

Caching can significantly reduce latency for responses that have been served before. In addition, by eliminating the need to compute a response for the same input again and again, we can reduce the number of LLM requests and thus save cost. Also, there are certain use cases that do not support latency on the order of seconds. Thus, pre-computing and caching may be the only way to serve those use cases.

An example of caching for LLMs is GPTCache.

When a new request is received:

Embedding generator: This embeds the request via various models such as OpenAI’s

text-embedding-ada-002, FastText, Sentence Transformers, and more.Similarity evaluator: This computes the similarity of the request via the vector store and then provides a distance metric. The vector store can either be local (FAISS, Hnswlib) or cloud-based. It can also compute similarity via a model.

Cache storage: If the request is similar, the cached response is fetched and served.

LLM: If the request isn’t similar enough, it gets passed to the LLM which then generates the result. Finally, the response is served and cached for future use.

Redis also shared a similar example, mentioning that some teams go as far as precomputing all the queries they anticipate receiving. Then, they set a similarity threshold on which queries are similar enough to warrant a cached response.

Guardrails: To ensure output quality

In the context of LLMs, guardrails validate the output of LLMs, ensuring that the output doesn’t just sound good but is also syntactically correct, factual, and free from harmful content. It also includes guarding against adversarial input.

Why guardrails?

First, they help ensure that model outputs are reliable and consistent enough to use in production. For example, we may require output to be in a specific JSON schema so that it’s machine-readable, or we need code generated to be executable. Guardrails can help with such syntactic validation.

Second, they provide an additional layer of safety and maintain quality control over an LLM’s output. For example, to verify if the content generated is appropriate for serving, we may want to check that the output isn’t harmful, verify it for factual accuracy, or ensure coherence with the context provided.

There are many approaches to setting up guardrails, check the second source mentioned in the beginning of this page incase you are interested in learning more.

Last updated